How does stacking empty cardboard boxes help someone whose home has been destroyed miles away?

The first thing most people think when they hear Oklahoma is tornado, and with good reason. In 2013, a tornado which broke records in both wind speeds and property damage leveled homes, businesses, hospitals, and schools in central Oklahoma.

In the hours and days afterwards, thousands of people flooded to the disaster area to help in any way they could. Average people were digging through piles of rubble to find survivors. Others helped the newly homeless find another place to sleep.

But actually, way too many people went to the area to help—so much so that they got in the way of first responders. Police shut down the area, and all the news channels pleaded for people to stay away from the disaster area. There were so many helpers that they were actually causing harm.

The fact is, most people—including you and me—would love to save a life in a crisis or do other impactful work. We earnestly want to make a difference, but we often define “making a difference” as doing something that looks important, gains us respect, and gives us a story to tell. In other words, the “best” kind of help seems to be the visible, heroic stuff. In the case of the tornado devastation, the help of thousands of people was needed, but for only a handful to be visible “heroes.”

A large church nearby did an impressive job of organizing volunteers to seek donated supplies, go pick them up, sort them, determine where supplies were needed, and deliver them. This required lots of computer work, phone calls, and other unimpressive jobs miles away from the houses that had been reduced to rubble. For most people to contribute to tornado relief, they needed to be indistinct, invisible cogs in a huge machine like this one; their united work could do more to help victims than any number of non-united individuals could have. The job that I was assigned there was to neatly stack empty supply boxes so that someone else could dispose of them.

There was actually no lack of volunteers for these cog-level jobs in the first several days, but they dwindled quickly, and the number of people who continued to go to the disaster area spoke to how insignificant people felt such jobs were. How does stacking empty cardboard boxes help someone whose home has been destroyed miles away? Could I honestly say that I was doing something significant?

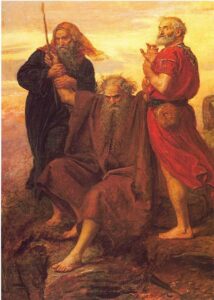

I’ll tell you another story from a not-often-discussed passage in Scripture (Exodus 17): The Israelite army, commanded by Joshua, battles against Amalek. Moses stands on top of a hill overlooking the battle and raises his hands to heaven. As long as his hands are raised, Israel does well, but when he lowers them, Israel gets beaten back. The battle goes on for hours, and Moses is unable to keep his hands up on his own. Eventually two men, Aaron and Hur, find a rock for Moses to sit on and help hold his hands up. Israel wins.

Now, who was most responsible for Israel’s victory (not including God)? It’s easy to see how different people in the story played a crucial role, but let’s be honest—Aaron and Hur had a pretty unexciting job.

Using this Bible story as a framework, let’s divide non-profit work into three categories. The first category we’ll call direct contact. This is the work that is the most visible: raising your hands so that God will grant your army victory, rescuing survivors from rubble, giving life-saving CPR, giving food to orphans, leading someone in prayer to place their faith in Christ, etc. Lives are saved and changed, and evil is thwarted. This is the “hero” job—the one that can feel the most rewarding and typically receives the most publicity and praise.

The second category we’ll call direct support. In other words, work that makes direct contact possible, like being an ambulance or fire truck driver (but not treating or rescuing anyone), cooking/donating the food given to orphans (but not being the one to give it to them), sharing the gospel with someone who doesn’t immediately place their faith in Christ, holding up Moses’ arms, etc. This position doesn’t catch as much publicity, but some praise can still be garnered because it’s easy to see how it facilitates the «important» stuff.

Let’s call the third category support support, as in the work that makes direct support possible. It typically happens out of sight of and at a different time than direct contact work. These are jobs like ambulance engine maintenance, child sponsor, or the purse-carrier to one of the hundred guys who buys bronze to be made into swords and shields for the Israelite army (or however that worked). Support supporters are the accountants, the media makers and AV techs, the donation-sorters, box organizers, phone-answerers, coffee-getters, legal counsel, building managers, janitors, and much more. When they are volunteers, they can have a hard time seeing their significance in the bigger picture. When they are paid, we sometimes call them overhead.

For the most part, support supporters aren’t heroes on their own, but their combined, organized force can be a critical part of making things happen. If we relate this to a human body, we see a great example in blood—a single blood cell has little to brag about, but blood is obviously vital to everything the body does.

So the «insignificant» support supporter who brags about their contributions is probably exaggerating, but they do contribute in a meaningful way. But isn’t the same true for the direct contactor, who is supported by an army of «blood cell»-level people? I think this is what the Apostle Paul means in Romans:

For by the grace given to me I say to everyone among you not to think of himself more highly than he ought to think, but to think with sober judgment, each according to the measure of faith that God has assigned. (12:3)

Sometimes you might be called to be Moses. Other times, you might be called to be Hur. Or a blood cell. Whatever your position, work diligently and judge carefully your true significance—you are valuable in whatever area you serve, but as one of many parts. Don’t assume you’re worthless; don’t assume you’re the star.